Lab 4: Digital Audio

Introduction

In this lab, a speaker was made to play music by toggling a GPIO pin at user-specified frequencies with the on-board MCU. More specifically, various C libraries were written from scratch so as to ultimately allow for interfacing between the MCU’s internal clock and timers. After taking in a system clock input of 80 MHz (the maximum possible PLL output frequency) and dividing it as necessary, one of the timers was used to generate square waves of variable frequencies, while another prolonged the existence of said square waves for specific periods of time. In other words: The first timer controlled the pitch of the song notes, while the other controlled the note durations. Additionally, a potentiometer was integrated into the MCU-speaker circuit to allow for user-dictated volume control.

Design and Testing Methodology

Firstly, the PLL was configured to take in the multispeed internal (MSI) RC oscillator as an input and output an 80 MHz clock signal. Then, timers TIM16 and TIM15 were set up to generate the PWM and mandate its duration, respectively. Finally, GPIO pin PA6 was chosen to actually output the square waves and interface with the physical world. (Note that some files were not originally produced and were instead taken from the solutions branch of an in-class activity.)

The two songs that the MCU was programmed to play were 1) Für Elise, as given in some Lab 4 starter code, and 2) Legendary; the sheet music for the latter was found online and was subsequently transcribed into more beginner-friendly notation by Alan Kappler.

Various tests were conducted on the final product, including both physical interaction with the resultant circuit and oscilloscope traces, as elaborated on in a later Results and Discussion section.

Technical Documentation

The source code for this project can be found in the associated GitHub repository folder.

Schematic

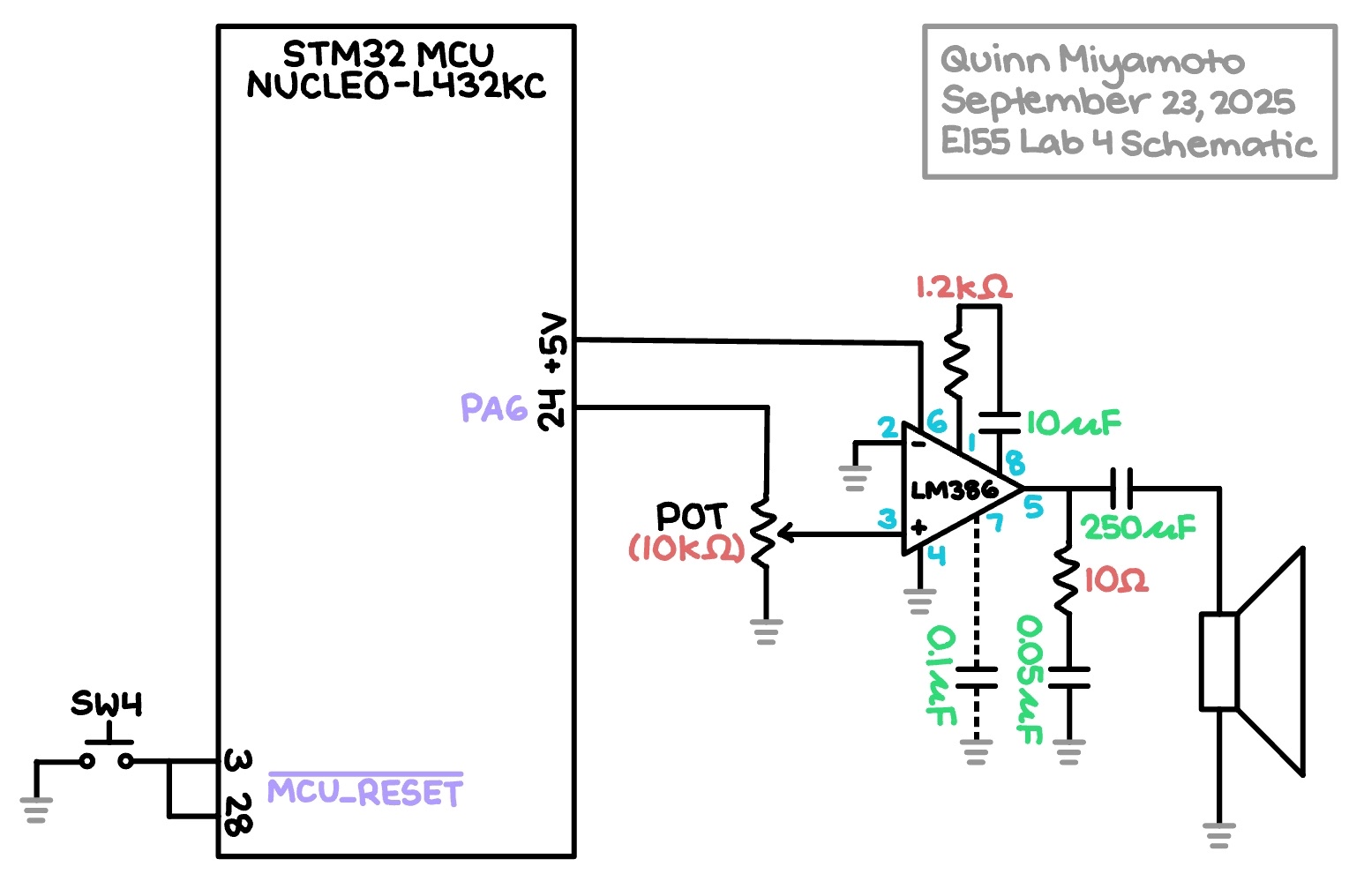

The Figure 1 schematic outlines how the physical components actually connect. All capacitor and resistor values were taken from an example circuit provided in the LM386 audio amplifier datasheet (specifically Figure 9-5, which depicts the LM386 with a gain of 50).

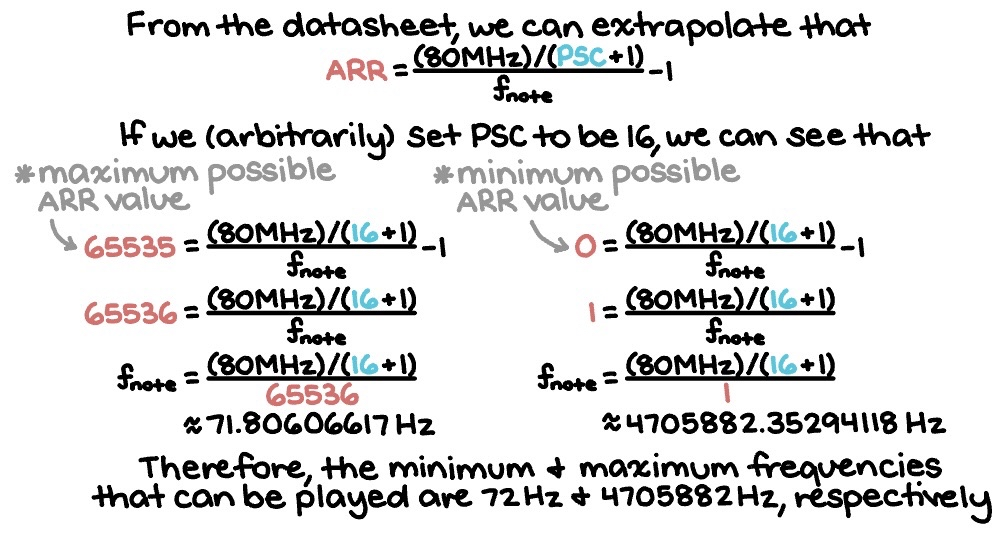

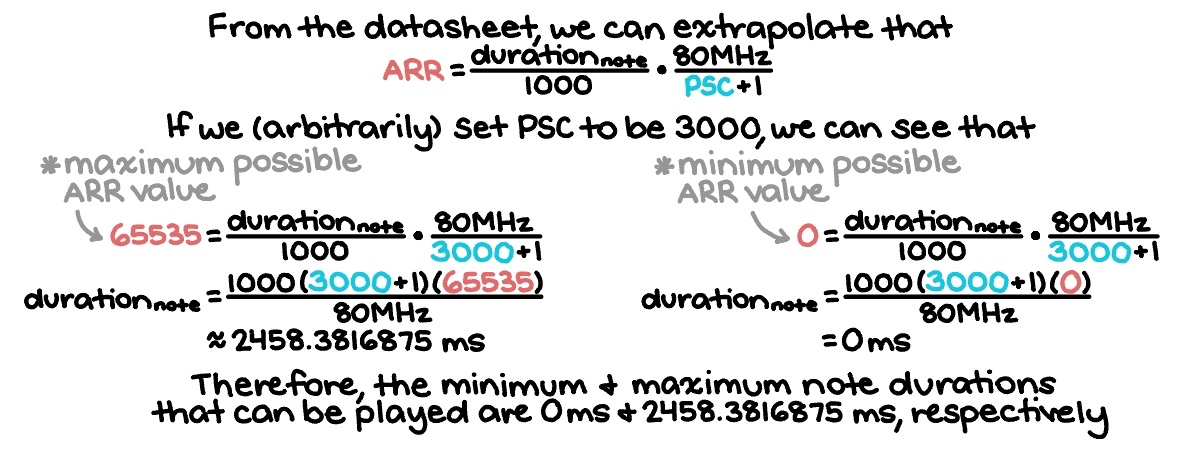

Minimum and Maximum Supported Frequencies and Durations

Additionally, the minimum and maximum possible frequencies and durations supported with the current prescaler values — what the internal system clock is ultimately divided by for the timer’s convenience — used in the code can be viewed in the following Figures 2a and 2b.

These computations were all performed with equations given in the STM32L432KC MCU reference manual. Most notably, the ARR value was relevant to all calculations because of the fact that it was the maximum number that any given timer could count up to before triggering an Update Interrupt Flag and exiting the C function.

Results and Discussion

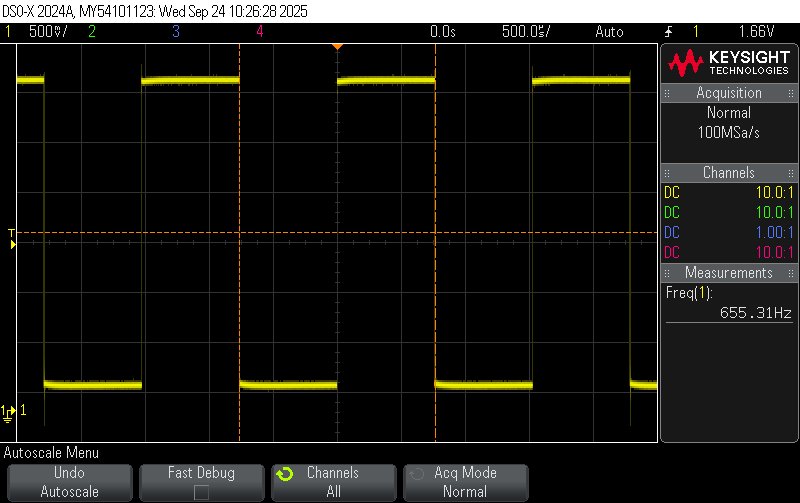

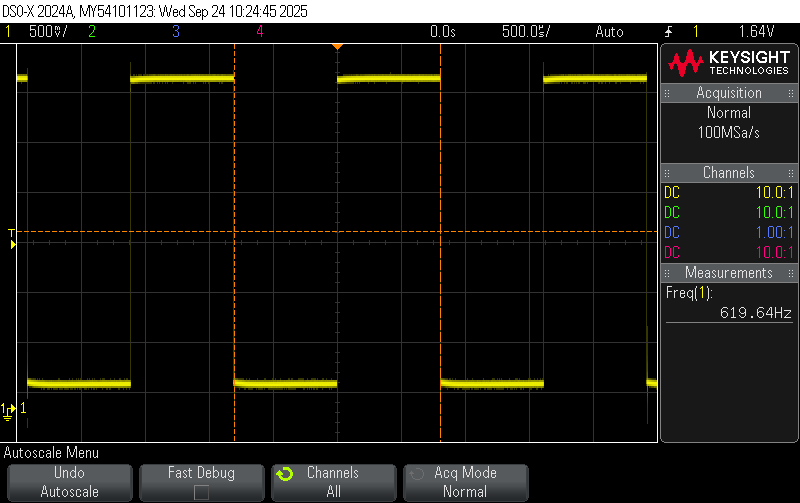

The results of Lab 4 can be viewed in Figures 3a and 3b below:

Evidently, all of the Lab 4 specs were met; all of the notes were the correct pitches and lasted for the appropriate durations. Although the specific potentiometer used didn’t allow for the finest volume control possible, it still worked well enough that it was deemed acceptable to keep.

Oscilloscope Traces

In order to verify that the speaker was outputting the correct pitches as intended, an oscilloscope was used to determine the actual frequencies being played for the first two notes of Für Elise. When compared to the expected values of 659 and 623 Hz, respectively, it was suffice to say that the design did, in fact, perform rather accurately.

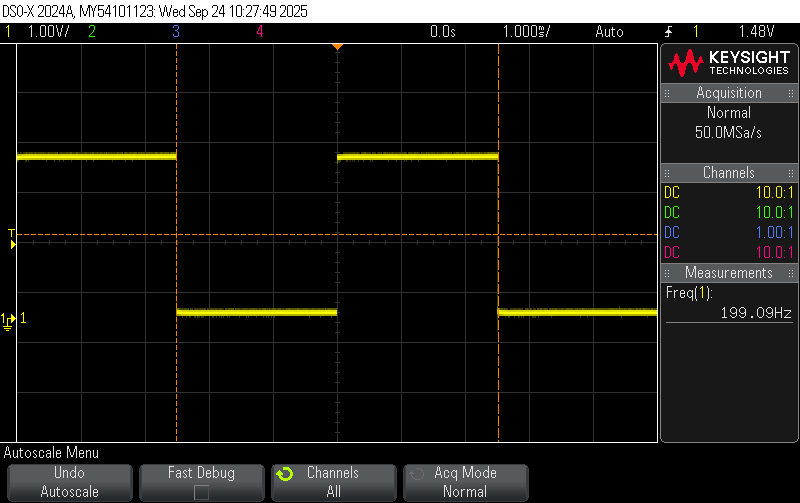

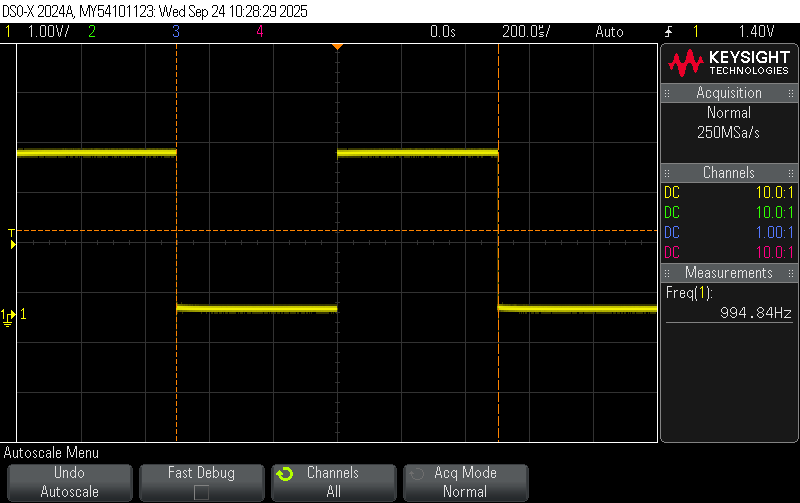

Furthermore, to really prove that the choice of the design was, without a doubt, completely functional, the speaker was forced to play both 200 and 1000 Hz signals — the bounds of an appropriately large frequency range, according to the specs — with the corresponding oscilloscope traces pictured in Figures 5a and 5b as follows:

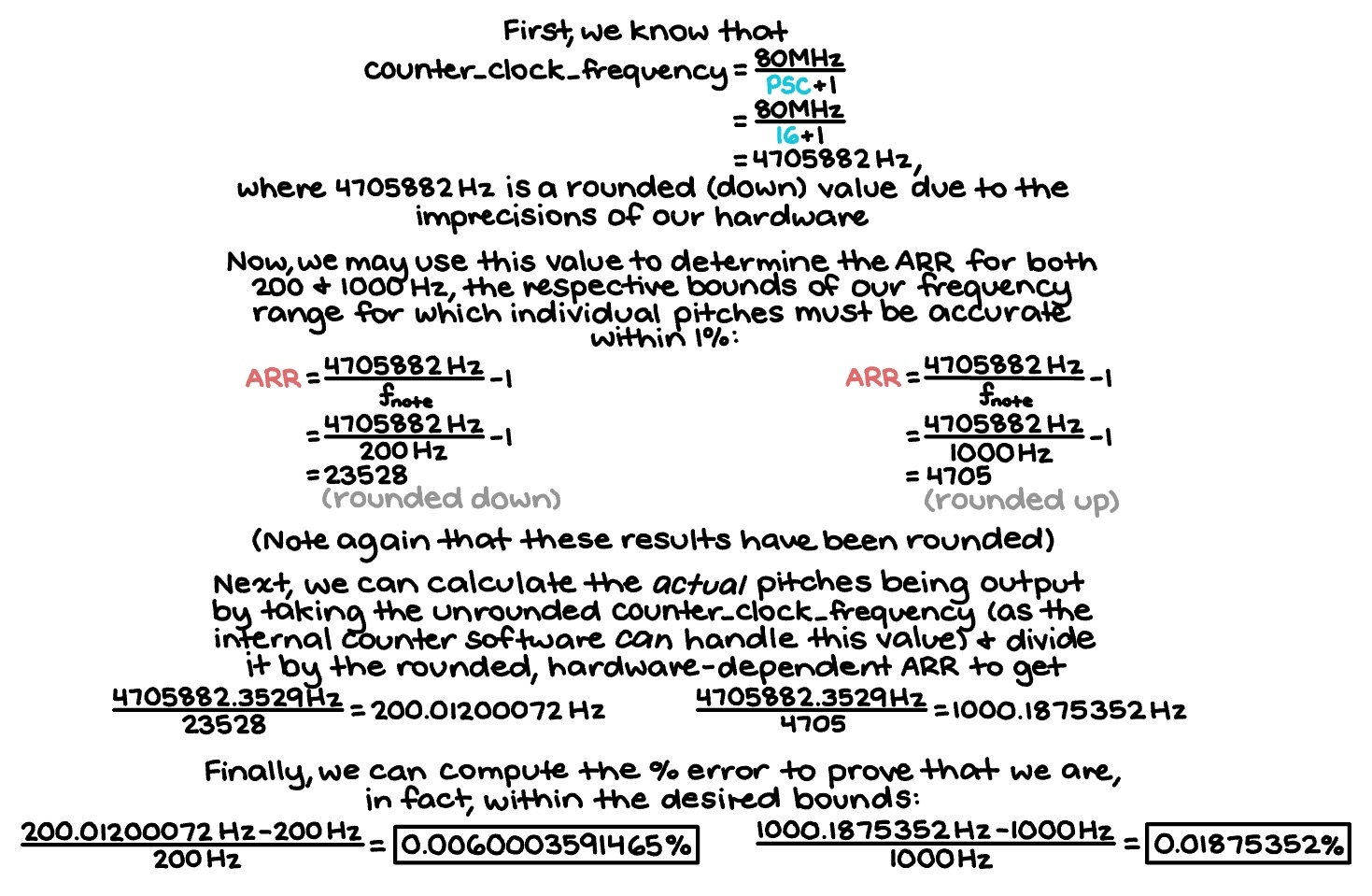

Finally, a few mathematical computations were performed in Figure 6 to quantify just how much percent error the actual output comprised when compared to theoretical results, and ultimately show that none of these values for the 200 to 1000 Hz frequency range were greater than one percent, as desired:

Conclusion

Overall, the design played both Für Elise and a composition of choice (Legendary) as required, with all notes having pitches and durations that were accurate to within one percent of the intended outcomes for the range of 200 to 1000 Hz. Additionally, a potentiometer was successfully incorporated into the circuit so as to allow for volume control. A total of approximately 15 hours was spent working on this lab.

AI Prototype

Using ChatGPT to generate some code in response to the prompt “What timers should I use on the STM32L432KC to generate frequencies ranging from 220Hz to 1kHz? What’s the best choice of timer if I want to easily connect it to a GPIO pin? What formulae are relevant, and what registers need to be set to configure them properly?,” the LLM produced surprisingly accurate results that can be viewed in the public chat transcript.

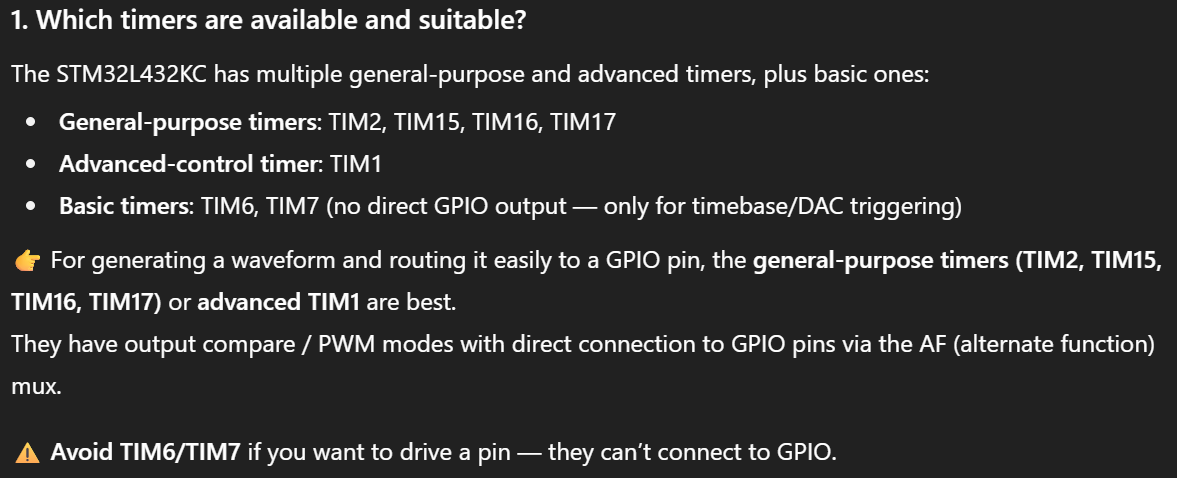

Most notably, the AI was correct in its timer overview (as depicted in Figure 7), with the recommended general purpose timers TIM15 and TIM16 being exactly what was used in the actual lab above.

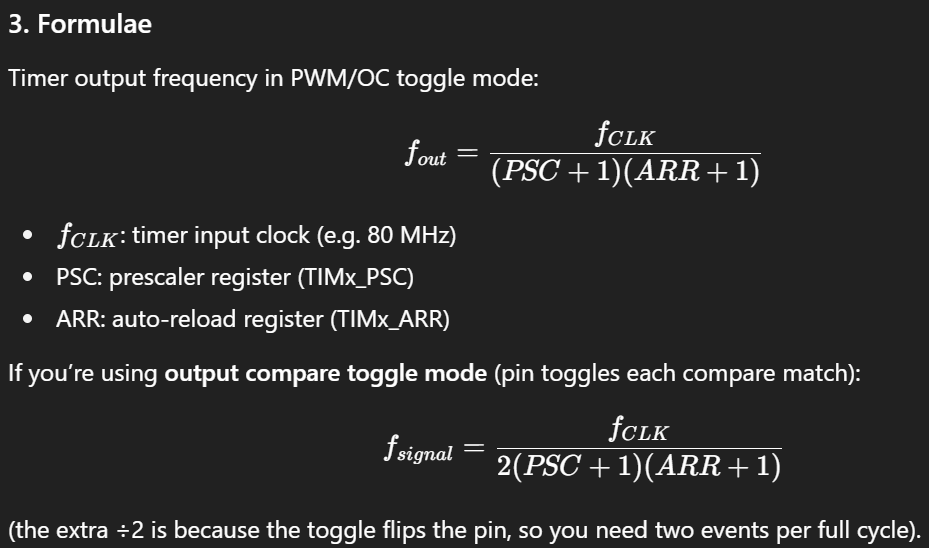

Furthermore, the provided formulae for both the note frequency and the duty cycle calculations were surprisingly correct. These are shown in Figure 8 below. The only things that were missing were the equations for ARR when trying to prolong the duration of a note.

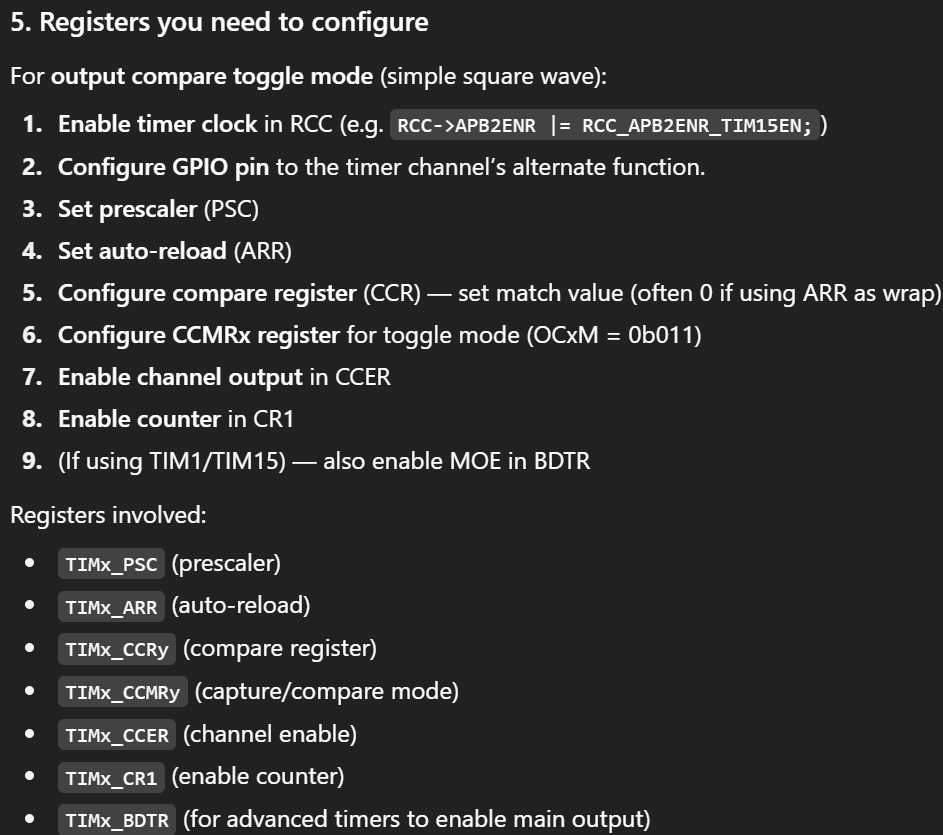

The LLM was also pretty accurate when it came to listing registers that needed to be configured, as seen in Figure 9. All of the registers it suggested were, in fact, necessary to consider; however, it did omit a few crucial ones. For instance, the Update Generation bit in the Event Generation Register was also rather important to set, as well as the SMS bits in the SMCR.

All in all, the quality of the output this time was extremely good, for it did not comprise any obvious inaccuracies. If the LLM-user was to approach this response with the mindset that it would provide a solid starting point but not everything that needed to be considered, it could prove to be invaluable help. The AI was definitely able to parse the reference manual at a far greater speed than any human could; it was even better at providing guidance than Ctrl-F (which, due to the sheer size of the manual, often missed things on not-yet-loaded pages).